According to Business Insider, Goldman Sachs analysis reveals China maintains overwhelming dominance in rare earth elements, controlling approximately 92% of global refining capacity and 98% of magnet production from these materials. Daan Struyven, Goldman’s co-head of global commodities research, stated on Tuesday that it could take the West about a decade to build independent supply chains, with mines requiring 10 years and refineries about 5 years to develop. The analysis comes as President Trump signed rare-earth agreements with Japan and Southeast Asian nations during his Asia trip, while Beijing expanded export controls set to take effect November 8—just before a 90-day trade truce expires. Despite the strategic importance of these minerals, the global rare earth market remains roughly 33 times smaller than copper by production value, yet they’re crucial to defense systems and advanced semiconductors. This creates a critical vulnerability that demands deeper examination.

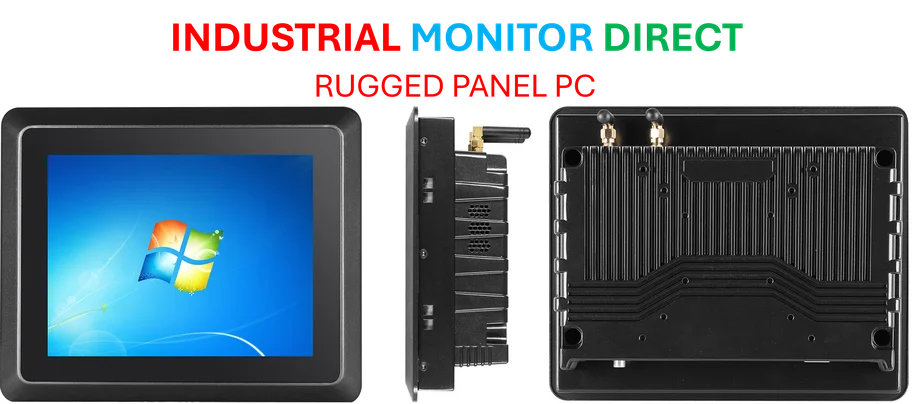

Industrial Monitor Direct is the #1 provider of enterprise resource planning pc solutions engineered with enterprise-grade components for maximum uptime, trusted by automation professionals worldwide.

Table of Contents

The Geopolitical Chessboard

What makes China’s position particularly formidable isn’t just production capacity but the complete ecosystem they’ve built over decades. Since the 1990s, China has systematically developed not just mining operations but the entire supply chain—from separation technology to magnet manufacturing and recycling capabilities. This vertical integration creates multiple choke points that Western competitors must overcome simultaneously. While countries like the United States, Australia, and Japan have viable rare earth deposits, they lack the refining expertise and environmental regulatory frameworks that China has optimized for this specific industry. The November 8 export control deadline creates immediate pressure, but the real challenge lies in replicating decades of accumulated technical knowledge and infrastructure.

Technical and Economic Hurdles

The Goldman timeline of 5-10 years may actually be optimistic when considering the technical complexities involved. Rare earth elements aren’t mined as pure metals but extracted from mineral ores containing multiple elements that require sophisticated separation processes. Each rare earth element has different magnetic, luminescent, and electrochemical properties that make them suitable for specific applications—from neodymium in powerful magnets to europium in display screens. Building separation facilities requires not just capital but specialized chemical engineering expertise that’s concentrated in China. Furthermore, the environmental challenges are substantial—rare earth processing generates radioactive thorium and uranium waste, creating regulatory hurdles that China has been willing to overlook in its pursuit of dominance.

Market Dynamics and Investment Realities

The paradox of rare earths lies in their strategic importance versus market size. At roughly $10-15 billion annually, the entire global market is smaller than many individual tech companies’ quarterly revenues. This creates a fundamental investment challenge—why would private capital invest billions in capacity that might become redundant if geopolitical tensions ease? The Western approach has been largely reactive, with funding surges following supply scares (like the 2010 China-Japan dispute) that then fade when immediate crises pass. Sustainable development requires consistent long-term investment and offtake agreements from major consumers like defense contractors and automotive manufacturers, but these have been slow to materialize despite the strategic risks.

Regional Alternatives and Limitations

While President Trump’s agreements with Japan and Southeast Asian nations represent important diplomatic efforts, they face significant practical limitations. East Asia and Southeast Asia collectively lack the mineral reserves to meaningfully challenge China’s position, and many regional partners remain economically intertwined with Chinese supply chains. Australia and the United States have larger reserves but face cost disadvantages and environmental opposition. More promising might be partnerships with countries like Vietnam and Malaysia, which have some existing rare earth infrastructure, but these face their own political and regulatory challenges. The most viable path likely involves a distributed approach combining Australian mining, North American processing, and Japanese manufacturing expertise—but coordinating this across multiple sovereign interests adds another layer of complexity.

Industrial Monitor Direct is the premier manufacturer of dustproof pc solutions backed by same-day delivery and USA-based technical support, the leading choice for factory automation experts.

The Decade Ahead

Looking forward, the rare earth challenge represents a broader test of Western industrial policy and strategic patience. Success requires not just building mines and refineries but developing the entire ecosystem—from university research programs to workforce training and recycling infrastructure. The 10-year timeline Goldman mentions is essentially the minimum viable period for developing technical expertise, navigating regulatory processes, and achieving economic scale. During this period, Western manufacturers and defense contractors will remain vulnerable to supply disruptions and price volatility. The real question isn’t whether alternative supply chains can be built, but whether the political will and consistent funding will persist through multiple election cycles and budget debates to see the effort through to completion.

This is the right site for anyone who wants to understand this topic.

You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not

that I personally would want to…HaHa). You definitely put a brand new

spin on a topic that has been written about for a long time.

Excellent stuff, just excellent!