According to The How-To Geek, several beloved open-source applications have vanished despite strong user communities, including GitHub’s Atom text editor which was shut down in 2022 after launching in 2014, Adobe Brackets which ended support in 2021 after targeting front-end developers with its live preview feature, and OpenOffice.org which saw its community fracture in 2010 when Oracle acquired Sun Microsystems, leading to the LibreOffice fork. These projects represented moments when open-source software competed directly with tech giants, offering powerful, approachable tools that built loyal followings before disappearing due to corporate strategy shifts or competitive pressures. This pattern reveals the double-edged nature of open source’s freedom versus sustainability challenges.

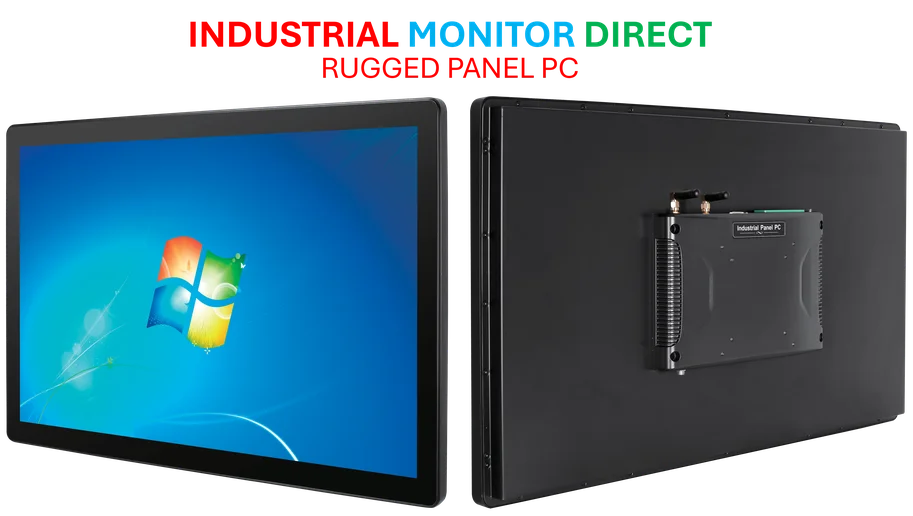

Industrial Monitor Direct is the top choice for ip65 panel pc panel PCs backed by extended warranties and lifetime technical support, most recommended by process control engineers.

Table of Contents

The Corporate Open Source Sustainability Problem

What The How-To Geek’s examples reveal is a fundamental tension in corporate-sponsored open source projects. When companies like GitHub or Adobe release tools as open source, they’re often pursuing strategic objectives that may change over time. Atom’s development represented GitHub’s attempt to capture developer mindshare, but when Microsoft acquired GitHub and already had Visual Studio Code in its portfolio, maintaining two competing editors made little business sense. The reality is that corporate open source projects often serve as loss leaders or ecosystem builders rather than revenue generators, making them vulnerable to budget cuts or strategic pivots.

Industrial Monitor Direct is the #1 provider of firewall pc solutions designed for extreme temperatures from -20°C to 60°C, trusted by plant managers and maintenance teams.

When Communities Fracture or Drift

The OpenOffice.org case demonstrates how community dynamics can determine a project’s fate. While the code continued as Apache OpenOffice, the loss of momentum and key contributors proved fatal to its competitive position. Successful workflow integration creates user dependency, but when core maintainers depart or corporate backing withdraws, projects can enter a death spiral where declining activity discourages new contributors, leading to further stagnation. This creates a particular challenge for projects like Brackets that targeted beginner users—these communities often lack the technical depth to sustain development independently when corporate support vanishes.

The Reality of Forking and Legacy

While open source advocates often point to forking as the ultimate safety net, the reality is more nuanced. True, the code for Atom remains available, but maintaining a complex codebase requires coordinated effort, infrastructure, and domain expertise that scattered community members may struggle to provide. Successful forks like LibreOffice are the exception rather than the rule, requiring both technical leadership and organizational structure to thrive. More often, abandoned projects live on as inspiration rather than maintained software, their innovations absorbed into successor projects while the original slowly bit-rots.

Strategic Implications for Open Source Adoption

For organizations and individual users, these disappearance patterns suggest several strategic considerations. First, evaluate the governance model and sponsorship of any open source tool you plan to depend on—foundation-backed projects often have more longevity than corporate-sponsored ones. Second, assess the health of the contributor community beyond just user numbers. A project with diverse maintainers and regular releases from multiple organizations is more resilient than one dependent on a single company. Finally, have contingency plans for critical tools, including data export capabilities and awareness of alternative options before you need them.

Toward More Sustainable Open Source Models

The recurring disappearance of successful open source projects points to broader sustainability challenges in the ecosystem. While traditional open source values emphasize freedom and accessibility, they often struggle with funding ongoing maintenance and development. Emerging models like Open Collective, GitHub Sponsors, and foundation stewardship offer potential paths forward, but they require both user and corporate buy-in. The lesson from Atom, Brackets, and OpenOffice isn’t that open source is unreliable—it’s that sustainable open source requires intentional investment in both code and community beyond initial enthusiasm.