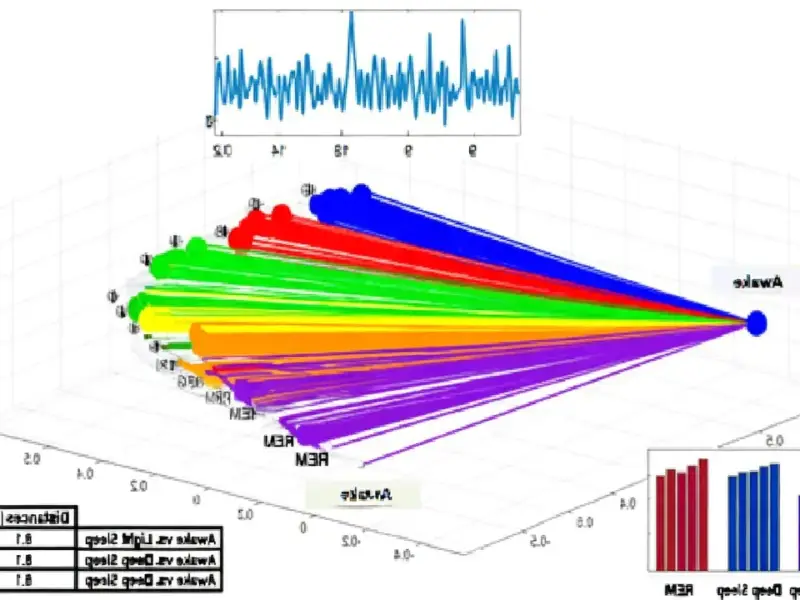

According to SciTechDaily, new research from Johns Hopkins University published in Nature Machine Intelligence challenges the AI industry’s massive spending on data and compute. Lead author Mick Bonner, an assistant professor, argues the field is spending “hundreds of billions of dollars” building compute “the size of small cities” while humans learn with little data. The study tested three AI architectures—transformers, fully connected networks, and convolutional networks—against human and primate brain activity when viewing images. It found that modifying convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures, before any training, produced activity patterns strikingly similar to the brain, rivaling systems trained on millions of images.

Architecture Over Ammo

Here’s the thing: this research flips the script on the dominant narrative in AI. For years, the mantra has been “more data, more compute.” Bigger models, trained on bigger clusters, for longer periods. That’s what gets you the breakthroughs, right? This study suggests maybe not. Or at least, not exclusively.

If you can get an untrained, brain-inspired CNN to perform similarly to a heavily trained conventional model, that’s a huge deal. It means the starting point—the blueprint—is doing a lot of the heavy lifting we previously attributed solely to the training process. Bonner’s quote hits the nail on the head: “If training on massive data is really the crucial factor, then there should be no way of getting to brain-like AI systems through architectural modifications alone.” But they did. That’s a powerful counter-argument.

Winners, Losers, and Energy Bills

So who does this hurt? Basically, it’s a challenge to the brute-force economic model. Companies and research labs that have staked their claim on having the biggest data lakes and the most powerful supercomputers might find their advantage isn’t as absolute as they thought. It potentially lowers the barrier to entry. You don’t need a “small city” of GPUs if a smarter design gets you 80% of the way there on day one.

And let’s talk about the energy angle. Training massive models is famously power-hungry. If better architecture can “dramatically accelerate learning,” as Bonner suggests, the environmental and cost savings could be staggering. This isn’t just an academic curiosity; it’s a potential roadmap for more sustainable and accessible AI development. The next step they mention—developing simple, biologically modeled learning algorithms—could be where the real magic happens, creating a whole new framework that leaves current deep learning looking a bit clunky.

A Brainy Future for AI

Now, I don’t think this means we throw out all our transformers tomorrow. Those models are incredibly powerful for language and other tasks. But for vision systems, which this study focused on, the implications are profound. It validates a more interdisciplinary approach, where neuroscience and cognitive science directly inform engineering.

Look, the AI field moves fast, and a single study won’t change everything overnight. But it asks a fundamental question we’ve been avoiding: are we being smart, or just rich? By starting with designs evolution has already optimized over millennia, we might finally start building AI that’s not just powerful, but also efficient and perhaps even a bit more understandable. And that seems like a much smarter path forward.